Sea Turtle Conservation

About Sea Turtles

There are seven species of sea turtles in the world. Four of those were found in Malaysia, namely: the Leatherback, Green, Hawksbill and Olive Ridley Sea Turtles. On Tioman Island, it has been 15 – 20 years since the Leatherback or Olive Ridley turtles have been found to nest here, and are therefore considered extinct from the area.

Leatherback Turtle

Green Sea Turtle

Hawksbill Turtle

The green turtle is now the most commonly seen sea turtle worldwide and on Tioman Island. Green turtles have a smooth carapace and vary in colour from grey, brown or black on top and a lighter yellow colour on their plastron. Adult green turtles feed on algae and sea grass mostly, while the hatchlings eat planktonic organisms and algae.

The hawksbill turtle is the only other type of sea turtle that is still found nesting on Tioman. Hawksbills are distinguished by their prominent hooked beak (like a hawk, or eagle) and their over-lapping scutes on the carapace. Hawksbills are amber coloured with black or brown accents and a white or light yellow plastron.

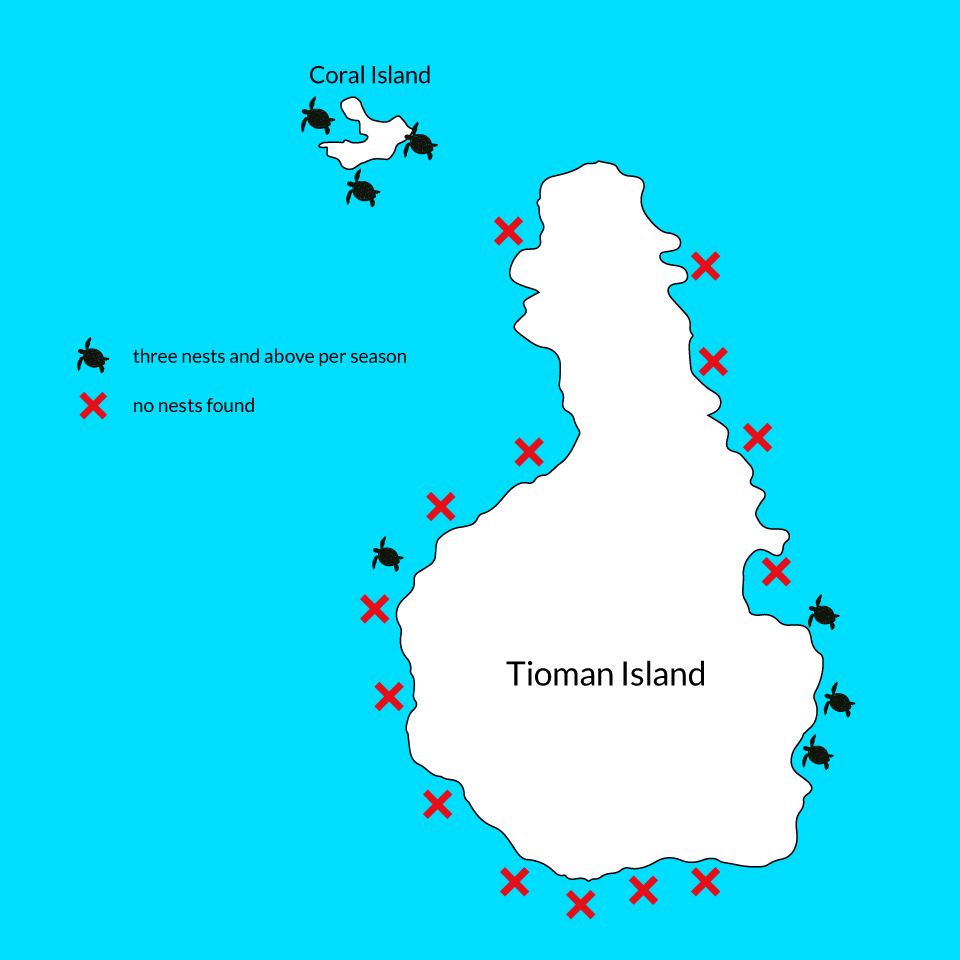

Sea Turtle Nesting Sites on Tioman Island

The largest species of sea turtle is the Leatherback, being able to reach up to 2 meters length. Leatherback turtles are also one of the deepest divers of the ocean; they have been recorded diving to 1200 meters deep. The only type of sea turtle that is not currently listed on the endangered species list is the Flatback sea turtle, native only to Australia, because is considered as Data Deficient, meaning there is insufficient scientific information to determine its conservation status at this time.

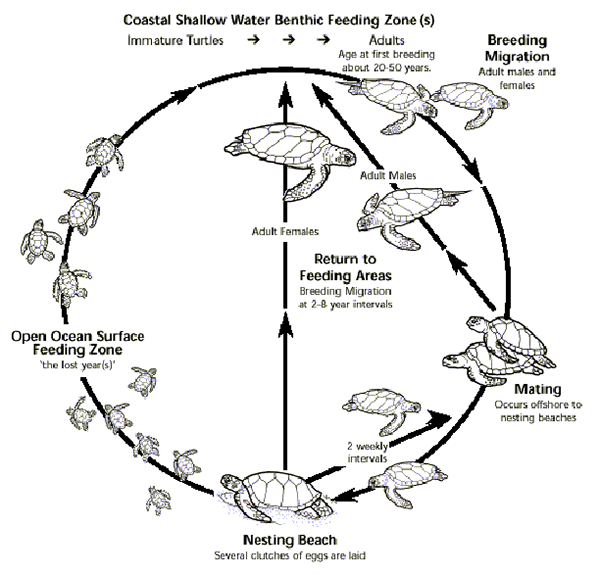

Life-Cycle of a sea turtle

A sea turtle’s life can be very long but it is also very strenuous. The eggs will incubate for 50 and 70 days before hatching (2 months), depending on the species of turtle. When a significant number of hatchlings have hatched in a nest, they will work together to dig up through the sand to reach the surface.

The eggs are at risk to animals, here mainly monitor lizards, and of course people. Once at the surface, hatchlings are at risk to predation from crabs, lizards, and birds, while in other parts of the world wild dogs, pigs and racoons threaten the hatchlings. On their way to the sea, sea turtle hatchlings use visual clues to find the ocean, following the brightest horizon. In any natural setting the ocean is brighter than the land, but in coastal developed areas, resorts, businesses and restaurants invade with lights brighter than the ocean. As a result, light distracts the hatchlings from the ocean, leading them away from the water and exposing them to dehydration or predation.

Source: Lanyon, J. M., C. J. Limpus & H. Marsh 1989

When the hatchlings reach the ocean they will swim for days and end up in ocean currents. They find food sources along the way, such as shrimp and crab larvae, but this food isn’t essential because they have back up energy for up to two weeks from the yolk sac which is absorbed when inside the egg. Sharks, large fish, and sea birds are natural predators for the new born turtles as they swim away from shore. Rubbish, like cigarette butts, in the ocean from human waste looks like food to the turtles and will kill the hatchlings if they eat it. Rubbish is, sadly, abundant in the ocean and many marine creatures are negatively affected by it. The turtles will swim and float along with ocean currents until the currents cross at the feeding grounds. This is where the young turtles find islands of sea grass and plants to hide inside from natural predators while they forage for insects, snails, fish larvae and small crabs.

Turtles in open water will migrate with ocean currents, some hiding with seaweed and others exposed, until they have grown to a size or age at which they return to coastal waters, usually between 5 and 10 years or when the shell has reached the size of a dinner plate.. When sea turtles find reefs close to the coast, their feeding habits are more adult like, meaning less intake and a change in diet. Each type of turtle has a specific common food, jelly fish for Leatherback turtles, sea grass for Green turtles, coral sponge for the Hawksbill.

Sea turtles take up a preferred feeding area, a home feeding ground, where they spend most of their time and return to the same feeding ground after nesting later in life, year after year. Depending on the species, sea turtles reach sexual maturity anywhere from around 10 to 50 years of age. This is a large reason why sea turtles are having trouble, because it takes very long time for them to be reproductive. Green turtles mature between 20 and 50 years of age whereas Hawksbill mature at around 30 years of age, and this is when the females can begin to lay eggs. Once sea turtles mature, both males and females leave their feeding or foraging grounds and begin their migration to their breeding grounds, where they will mate and begin the reproductive stage of their lives. Only females come ashore to lay eggs, usually near the area where they hatched perhaps two or more decades earlier.

The eggs are fertilised by the males in the ocean. The female then emerges from the ocean, normally at night, to lay her eggs. The beach where the nesting turtles were born was once a suitable place for their nests, but after 35 years, the beach may have changed. Hotels, boats, concrete, and people could now be on the beaches where the turtles used to lay their eggs. If a sea turtle is unable to find a suitable beach to lay their eggs, they finally abort the eggs into the ocean.

When the female sea turtle is ready, she will approach the the beach, usually at night, and crawl up close to the vegetation line. She will then clear a space with her front flippers, then dig a big pit, anywhere from a few inches deep to a half a meter deep as he green sea turtles do. Inside the pit, the nesting female digs the egg hole with her back flippers. This hole is about 20cm across and between 50 and 60 cm deep, dug with the hind flippers. The eggs are laid into the hole and then covered with sand using the back flippers again. Green Turtles lay around 120 eggs while a Hawksbill can lay up to160 eggs on average. She then returns to the sea, ready to mate again to lay more eggs. Most species will nest several times during a nesting season every 2-4 years over the course of their lifetime.

It is not known exactly how long sea turtles live in the wild, but scientists think their life span may be as long as a century.

Threats

Every year thousands of hatchling turtles reach the ocean from their nests along the Malaysia’s coast. Sadly, only an estimated 1 out of 1,000 to 10,000 will survive to adulthood. There are natural threats affecting sea turtles both on the beach and on the ocean, but it is the increasing threats caused by humans that are driving them to extinction. Today, all sea turtles found Malaysia’s waters are listed as endangered or critically endangered by the IUCN.

Natural threats

In nature, sea turtles struggle for their survival facing countless obstacles through their entire life. Predators such as monitor lizards, crabs and ants raid eggs and hatchlings still in the nest. Once they emerge, hatchlings make bite-sized meals for birds, crabs and innumerable predators in the ocean. Once sea turtles reach adulthood, they are relatively less vulnerable to predation, except for the biggest predators in the ocean, such as sharks or orcas. These natural threats, however, are not the reasons why sea turtle populations have dropped catastrophically to face the extinction.

Human or Anthropogenic threats

The threats are driving sea turtles to the extinction are all caused by humans.

Harvest for human consumption

In many coastal communities, especially in South East Asia, Central and South America, and Africa, sea turtles have been for years an important source of food. In Asia, fishermen used to take sea turtles from the ocean to keep them on board as a source of food for the crew. They could spend days or weeks feeding on the meet from just one turtle. In Peninsular Malaysia is very rare to kill a sea turtle for consumption, but in other areas of South East Asia, this practise is very common. Additionally, people may use other parts of the turtle for making products, including the oil, cartilage, skin and the carapace. All sea turtle species are hunted in some areas for their flesh or for their beautiful carapace. The hawksbill’s carapace, known as tortoiseshell, is particularly in demand and is used to make jewellery, such as necklaces, bracelets or sunglasses.

Photo: legallized egg collection in Ostional, Northwest of Costa Rica. Source: http://coastalcare.org

Therefore, during the nesting season, people patrol the beaches at night looking for nesting females and their eggs. Sea turtle eggs have been in the past an important source of food for local communities, especially for those living in remote areas, and in some way it used to be a sustainable way of living. However, right know there is an important trade of turtle eggs making sea turtle population don’t have enough time to recover. Many countries have forbidden the illegal egg collection. In Malaysia, only in Sabah and Sarawak states illegal egg collection and consumption of eggs of all species are banned. In Peninsular Malaysia, however, sea turtle eggs are considered a delicacy and each state makes its own legislation about egg collection and consumption.

Commercial fishing industry: longlines, trawling and gill nets

Every year hundreds of thousands of sea turtles are accidentally captured by the commercial fishing industry (bycatch), but it is not well known how many turtles are captured yearly. However, it is estimated an annual sea turtle capture, injury and mortality of around 150,000 turtles killed in trawl nets, especially from the shrimp fishing industry, and more than 200,000 sea turtles captured or killed by longlines and gill nets. The amount of turtles dead by gill nets is unknown, but sea turtle capture is significant where studied, suggesting the sea turtle mortality in gill nets may be comparable to trawl and longline mortality.

Photo: Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) entangled in a fishing net in the Mediterranean Sea. Photo credit: Jordi Chia’s / natural.com

Turtles are affected to an unknown, but potentially significant degree, by entanglement in persistent marine debris, including discarded or lost fishing gear including steel and monofilament line, synthetic and natural rope, plastic onion sacks and discarded plastic netting materials.

Plastic debris ingestion

From the last few decades, marine life is struggling due to the increasing presence of plastic debris in the ocean. Is estimated that over 1 million marine animals, including mammals, fish, sharks, turtles, and birds, are killed each year due to plastic debris. The majority of this plastic comes from land, and through the river, it finally ends up in both ocean and beaches. As a result, sea turtles mistake these plastics for food and accidentally swallow them. Considering sea turtles are one of the main predators for jellyfish – especially green turtles and leatherbacks – they accidentally may mistake jellyfish and floating plastic bags.

Some plastic debris can be easily recognized by human eye, such as plastic bottles, plastic bags, packaging plastics, glasses and a huge etc. However, most of the plastics present in the ocean are invisible for human eye – less than 1mm –. These plastic particles are called microplastics, and they can be found everywhere, but mostly on the sediments. If sea turtles feed on these particles, they can become sick or even starve to death. In 2017, JTP conducted a necropsy of a juvenile Green turtle which was found in a very poor condition in Ayer Batang. The content found in its stomach was mainly string and fishing line pieces, foam pieces and microplastics.

Habitat loss

Sea turtles spend most of their life time in the water, but principally near the coast. They will migrate very long distances to find their food, to mate or to lay their eggs. From last few decades, due to the increase of tourism and their demands, coastal areas over the world have developed significantly adding an enormous pressure into sea turtle habitats. With the increase of coastal development, sea turtles have to compete with tourist, businesses and restaurants to use the beach.

In tropical areas, where coral reefs or seagrass meadows used to be pristine, human pressure has led to an important deterioration of these ecosystems, causing them more difficulties to find their food.

Therefore, sea turtles rely on dark nesting beaches to lay their eggs. The beach where the nesting turtles were born was once a suitable place for their nests, but after 35 years, the beach may have changed, resulting in artificial lightning on the beach that disrupts sea turtles from nesting. If a sea turtle is unable to find a suitable beach to lay her eggs, she will abort the nest into the ocean. Also, artificial lightning causes sea turtle hatchlings to become disoriented on their way to reach the ocean, relaying them to wander on the beach where they often die of dehydration or predation.

And last but not least, it is important to highlight other human threats such as beach activities, marine pollution or climate change.

Human use of nesting beaches for recreational activities can impact negatively to sea turtles. Firstly, night time human activities can prevent sea turtles to emerge from the sea or cause female turtle to stop their nesting process. Therefore, the use of vehicles such as cars or quads can cause sand compaction above the nests making more difficult to the hatchlings their emergence. In addition, day-time water recreational activities such as boat-activities, jet-sky activities threat sea turtles even more than night-time activities as many turtles are killed or injured by accident every year. When turtles surface to breathe, they are exposed to boats, propellers, barges, and jet skis, causing fatal collisions to the turtles.

Photo: Juara Bay night view, 2018. Photo credit: Alberto Garcia

Marine pollution can impact severely sea turtles and the food they eat. Oil spills, fertilizers and chemicals from industrial agriculture all contribute to pollute the water, contaminating the seagrass and the food in general sea turtles consume.

Sea turtle sex ratio depends on the temperature within the nest. In normal conditions, average incubation temperatures ranges between 29 to 30°C what determines around 50% of each gender. Increasing the incubation temperature can result in a sex ratio imbalance producing more females than males, which reduces the reproduction opportunities and decreases the genetic diversity of the species.

Fertilizers and chemicals from agriculture are dumped into the ocean through the rivers and land lixiviates, resulting in a significant increase of nutrients in the water. These nutrients are the source of food for algae and as the nutrient concentration increases the algae concentration increases too, causing harmful algal blooms -commonly called red tides- . Some of these algae produce toxins that are released into the water or are digested by preys of sea turtles. As a result, sea turtles can be affected by the toxin ingestion causing their death.

What We Do

Beach monitoring

Different nesting beaches around Tioman Island are monitored from March to October. The monitoring of the beaches is carried out on foot or by boat, dependent on the location, and since the re-nesting period of the sea turtles in the island is very accurate, it is possible to predict when the nesting turtles will return to lay another nest.

Night and morning patrols

Night patrols consist in one or several volunteers/staff members walking the beach from one side to the other checking for turtle activities. Mentawak and Barok beaches are patrolled every night during the nesting season.

Morning patrols are the most consistent way to monitor the beaches. They are carried out every day until the end of the season. Every morning at 5:30 a.m. the beaches were surveyed again in case of new turtle activities. Penut and Munjur were monitored every morning at 08:00 a.m. by boat as they are not accessible by walking. It takes around 20 minutes to get there (depending on the weather conditions). In Coral Island, the surveys consisted in morning patrols at 6 am.

In order to estimate the size of the nesting turtle population, information of nesting females and their nests are recorded during night patrols. These data is recorded at night in a waterproof notebook and includes: Date, Species, Beach, Sector, Time, Tags (new or existing), Curved carapace length (CCL), Curved carapace width (CCW), Nest depth (cm), Number of eggs, Width of the track and a body check to determinate any damage or distinctive features of the turtle.

Hatchery management

Some threats still affect sea turtle eggs in Tioman Island; unfortunately, if a nest is left in situ, the chances that it will be taken by poachers or predated by monitor lizards are very high. Measurements are taken from the original nest to try to reproduce the same conditions in the hatchery. The eggs are carefully transferred from the original nest into a relocation box and from it to the hatchery.

Relocated sea turtle nest inside fenced hatchery

After 50 days of incubation period, 10 days before a nest is expected to hatch, the hatchery is checked by visual observation multiple times per day. When all the hatchlings emerge from the nest, they are released few meters before the tide line. This is important for the hatchlings to strengthen the muscles of their flippers on their way to the sea and orient themselves through visual, chemical and mechanical cues. Moreover, it is a great opportunity for staff and volunteers to raise awareness among the tourists and locals who join the release.

In some conservation projects around Asia it is common to keep the hatchlings for weeks or months in tanks until they increase in size before releasing them (this practice is known as “headstart”). In JTP, we try to reproduce the natural life conditions of sea turtles as much as possible so we chose to release them as soon as they hatch. In addition, raising them up in captivity can affect their natural instincts and make it more difficult for them to survive in the wildness.

Excavation of nests

The excavation and analysis of the contents of unhatched eggs is crucial to determine the reproductive success of each nest, the incidence of natural predators and the effectiveness of the hatchery management and relocation protocol used in the project. All nests in the hatchery are excavated at 3 days after first hatching. The aim of an excavation is, 1) to determinate the hatching success rate (HSR), 2) the emergence success rate (ESR), and 3) to evaluate why some eggs didn’t hatch.